Exclusive excerpt from new book by Rolling Stone contributor Gavin Edwards

October 22, 2013 9:00 AM ET

It’s been 20 years since the death of River Phoenix at age 23. In Last Night at the Viper Room, out today, Rolling Stone contributor Gavin Edwards tells the story of the actor-musician’s brief life and tragic death. This exclusive excerpt from the chapter “If the Sky That We Look Upon Should Tumble and Fall” recounts Phoenix’s experience on the set of Stand by Me, the coming-of-age movie that made him a star, featuring interviews with co-star Corey Feldman, director Rob Reiner and more.

“Chris Chambers was the leader of our gang, and my best friend. He came from a bad family, and everybody just knew he’d turn out bad – including Chris.” That was how Richard Dreyfuss, narrating as the adult Gordie Lachance, described the character in Stand by Me that made River Phoenix a star.

River had been treating acting as a lark – he enjoyed doing it, but music remained his first love. After wrapping Explorers, however, he was fooling around on a motorcycle, racing it in a dirt field, and he took a spill, tearing up a tendon in his left knee. The injury gave him plenty of time to sit on the couch, thinking about life. River had an epiphany: acting in movies was not just a fluke detour in his life, it was important to him, and he wanted to do it well. Before he was fully healed, he went on an audition for Stand by Me. “I kind of limped in,” River said, but he thought that the injury ultimately helped him land the part. “I had this tragic air to me ’cause I was bummed out by the accident.”

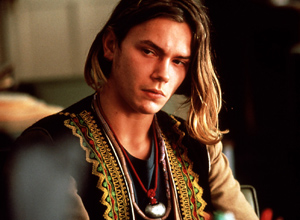

River’s character was tough, sensitive, and just a little goofy. In blue jeans and a white T-shirt, sporting a short Fifties haircut, he looked like a screen star of the past – one in particular. Director Rob Reiner said, “He was a young James Dean and I had never seen anybody like that.”

Wil Wheaton, who played the 12-year-old Gordie, said that the movie worked, in large part, because the four young actors starring in it matched their characters so well: he was nerdy and uncomfortable in his own skin; Jerry O’Connell was funny and schlubby (looking nothing like the chiseled hunk he became as an adult); Corey Feldman was full of inchoate rage and had an awful relationship with his parents. “And River was cool and really smart and passionate,” Wheaton said. “Kind of like a father figure to some of us.”

At first, Wheaton was intimidated by River, who was 14 to his 12. He explained, “He was so professional and so intense, he just seemed a lot older than he was. He seemed to have this wisdom around him that was really difficult to quantify at that age.” He was smart, he was musically talented, and he was one of the kindest people Wheaton had ever met. In other words: “He just seemed cool.”

Stand by Me, based on the Stephen King novella The Body, is the story of four boys in small-town Oregon in 1959. Just before junior high school begins, they hike 20 miles down the train tracks to the spot where they have heard the corpse of a missing kid lies, and come home older and wiser.

Production began on The Body (as it was then known) in June 1984. Reiner, most famous for playing “Meathead” on All in the Family, had already directed This Is Spinal Tap and The Sure Thing. He didn’t think a coming-of-age period piece had much commercial potential, but it was the sort of movie he wanted to make.

Reiner gave his stars tapes of late-Fifties music and made sure they learned the slang of the era. More importantly, he summoned his four young leads one week early to Brownsville, Oregon (about a hundred miles west of where River was born, on the other side of the Cascade Mountains). Reiner led them in games drawn from Viola Spolin’s book Improvisations for the Theater: River and the other boys mimed each other’s gestures as if they were mirror images, told collaborative stories, and took turns guiding each other blindfolded through their hotel lobby. “Theater games develop trust among people,” declared Reiner, who needed his four actors to become friends – quickly.

Feldman had known River a long time – they had become friendly on the L.A. audition circuit. “Whenever we saw each other on auditions,” Feldman remembered, “we would hang out or play outside while everyone else was sitting in the room waiting for their shot.”

The quartet soon bonded. When The Goonies, starring Feldman, was released that summer, they went to see it together; a few weeks later, they all went to Explorers. Wheaton’s family organized weekend white-water rafting trips for the cast and crew. At the end of one outing, they found themselves at a clothing-optional hot springs that was hosting a hippie fair; some of the cast got to juggle with the Flying Karamazov Brothers.

At the hotel, the actors were testing their limits. When River found out Wheaton was adept with electronics, he encouraged him to monkey with a video-game machine so they could play for free, promising that he’d take the blame if they got caught. They soaked Feldman’s wardrobe in beer; after his clothes dried, he smelled like a wino. And they threw the poolside chairs into the hotel pool – the closest four well-meaning young adolescents could get to acting like the Who.

Kiefer Sutherland had a supporting role as the quartet’s nemesis, a juvenile delinquent named Ace Merrill. Sutherland was almost four years older than River, and spent most of his time on set in character, so the two actors didn’t get to know each other very well. Nevertheless, on a day when River was in a destructive mood, he bombarded Sutherland’s car with large dirt clods until it was covered in muck. “The other guys dared me to do it,” River explained. “They knew it was Kiefer’s car – I didn’t. When I found out, I was scared for my life.”

Soon after, Sutherland spotted River at a local restaurant and called him over to his table. Terrified, River blurted out, “Kiefer, I’m really sorry.”

Sutherland was confused; he was just saying hello. When River explained he was the culprit behind the dirt-clod fusillade, Sutherland laughed and said, “Don’t worry about it. It’s a rental car – they washed it off.”

River was relieved, having conflated Sutherland with his character: “I didn’t know if he was going to pull out the switchblade and slit my throat.” Feldman and River checked out a local underage nightclub. Feldman said, “There was no alcohol served there or anything, but of course, all the kids were drinking anyway.” The locals offered booze to the visiting Hollywood actors and, with the lightest touches of peer pressure, got them to take their first drinks.

“Kids never got along with me,” River said. The experiences that had made his life extraordinary had also made it impossible to find common ground with regular teenagers. “These kids, because this was Oregon and not L.A., and because we were actors and they admired us or whatever, they’d do anything to appease us. So they got me a forty-ouncer of beer, which I drank straight down just to show them. The only other thing I remember about that night was laying on the railroad tracks with everything spinning all around me.”

Feldman said that he and River also had their first significant marijuana experience together. They were hanging out in another hotel room, this one occupied by one of the movie’s technicians. When the two kids spotted a bong in his closet and asked what it was, he not only explained its purpose and workings to them, he (with what seems an astonishing lack of adult responsibility) let them try it out. Feldman recalled, “We both coughed a lot and had sore throats – but even though we were kind of bouncing off the walls of the hotel, neither of us seemed to be affected by it. It didn’t change our state of mind in any way.”

The coda: Some months later, when the Stand by Me cast stayed in a New York City hotel for the movie’s press junket, a distinctive aroma was wafting from River’s room. “I could smell the pot coming all the way down the hallway,” Feldman said. River laughed it off, saying it was somebody else’s.

River turned 15 while shooting Stand by Me, and seemed determined to grow up just as decisively as the movie’s characters. The four young actors talked about sex all the time, despite (or because of) their lack of experience. “Sex was nearly all that River could think about,” Feldman said.

River had a major crush on a friend of the family, an older teenager; the feeling was apparently mutual, since she propositioned him. “He decided it was time to end his self-imposed ‘second virginity’ and get on with his first teen sexual encounter,” Feldman said. River and his friend went to his parents to get their blessing – Arlyn and John not only consented, they pitched a tent in the backyard of their rented house and decorated it to enhance the mood.

“It was a beautiful experience,” Arlyn said later.

“A very strange experience,” River said. “I got through that, thank God.” He wasn’t just relieving his teenage hormones: he was attempting to have a mature sex life uncolored by his experiences with the Children of God. His emotions may have been mixed, but he was outwardly overjoyed: the next day on the set, he was telling the news to anybody who would listen. He even wrote a letter to Explorers director Joe Dante, who knew about River’s unslaked teenage lust, with the caps-lock on his handwriting: “WELL IT HAPPENED. IT FINALLY HAPPENED.”

Although the cast and crew remember the idyllic shoot of Stand by Me as the best summer ever, they were also making a quiet little movie that would turn out to be a masterpiece. The movie is saturated with issues of mortality – even if the boys treat their journey like an impromptu camping jamboree, they are looking for a dead body – but the flip side is that it has an unusually warm, generous sense of what it means to be alive. Stand by Me is full of quotable lines (“Mickey Mouse is a cartoon. Superman’s a real guy. There’s no way a cartoon could beat up a real guy”), but the foundation of the movie is the friendship between Wheaton’s Gordie and River’s Chris.

The defining scene for Chris comes when, late at night by a campfire, he confesses his fear that no matter what he does, the town will always think of him as “one of those low-life Chambers kids.” On the night the scene was shot, River delivered the monologue, telling the story of how he stole milk money from his school and then had moral qualms and returned the cash to a teacher – only to have her keep the money for herself, letting him take the blame and a three-day suspension.

Reiner wasn’t satisfied with River’s performance – it seemed emotionally flat. Sometimes he would act out dialogue himself so his young performers could hear what he was looking for, but this time Reiner had a quiet word with River, asking him, “Is there a moment in your life where you can recall an adult letting you down, and betraying you in some way? You don’t have to tell me who it is. I just want you to think about it.”

River walked away from the camera, replaying memories in his mind. A few minutes later, he returned and told Reiner he was ready to try again. This time his performance felt like an open wound: River wept while anger and pain roiled him. After the scene, Reiner went to River, who was still crying, gave him a big hug, and told him he loved him.

“It took him a while to get over it,” Reiner said. “Obviously, there was something very hurtful to him in his life that he connected with to make that scene work. You just saw that raw naturalism. I’ve seen the movie a thousand times – and every time I see that scene, I cry.”

Although River always praised the finished film (which changed titles from The Body to Stand by Me when marketers at Columbia Pictures worried that audiences would think it was a bodybuilding movie or a horror flick), he wasn’t so happy with his own performance. “Personally, I didn’t think my work was up to my own standards,” he said. Perhaps he felt that by drawing on his wellspring of pain and betrayal, he had exposed his secrets to the world. “I was going through puberty and I was hurting real bad,” he said of his emotional nakedness. “It’s not easy watching yourself so vulnerable.”